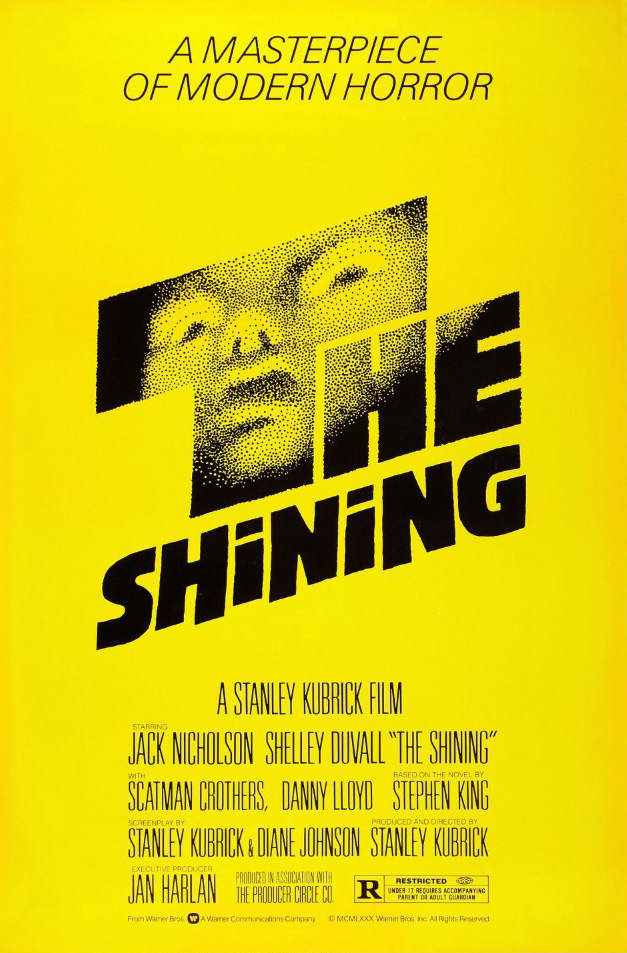

THE SHINING

The Shining (1980) is extraordinarily impressive visually: it was made with a Steadicam when the Steadicam was brand new technology, and Stanley Kubrick, the greatest of directors and once a professional photographer, is like a kid with a new toy, using the new possibilities to the fullest – the camera movement hypnotises, revolutionary at the time and setting the templates for imitation (alongside Halloween), as the camera sweepingly follows the child at the centre of the story on his play tricycle as he rides along hotel corridors, or it creeps over long distances into rooms and around corners as though a person, often becoming the characters’ viewpoint, etc, in a way that was not possible before the Steadicam – The Shining is also brilliant in terms of genre-bending: it plays with the Gothic (esp. in its contrary use of white and bright colours rather than the usual gloomy darkness of the genre) and Freud’s psychiatric notions of the uncanny, and takes the Gothic genre beyond the big empty house and ghosts to somewhere darker (metaphorically) and deeper – reportedly, Stephen King (on whose book it is based) was not happy with what was done to his text by the finished film, but Kubrick created something greater and with more depth than the simple Gothic formula of King (and, no doubt, King is now reconciled to the heaps of money and notoriety it has made him) – Kubrick never made a film without allegorical and/or thematic purpose and The Shining surpasses the standard Gothic horror imagery, with depths of meaning about the rapacious heart of mankind and numerous tales told about the hotel to create the hotel as a symbol of the violent history of humanity (see Room 237, a documentary about it for more) – the key to the subtext is to understand who the Caretaker is in Kubrick’s vision (as an image, we all are beneath our civilised surface) – and then there is the theme of a dysfunctional family unit, a tale of domestic abuse, with Jack Nicholson (also called Jack in the film) emitting sinisterly aggressive signals as the father, making you uneasy about him from the outset, teetering into surface aggression as the film progresses, his central performance reaching the extremes necessary to sell the more outré elements of the script, so hammy it verges on genius, as he loses his mind – and the film is full of symbols and quickly intercut images: the elevators let flow blood (what is it with elevators as a sign of demonic activity?) with rapid cuts to Danny (the family child) in terror with spittle hanging from his mouth; a maze and its model reflect the complex-yet-unravelling mind of the lead protagonist; Room 237 is the evil heart of the hotel; etc – there is also a fantastic soundtrack with original music provided by Wendy Carlos, the great pioneer of synthesiser music – and the locations and décor are picturesque yet with a hard-to-put-your-finger-on-why they are unsettling, very subtly feeling wrong and right at the same time – even the usually drab and uninteresting Shelley Duvall is astutely cast as the whimpering, mousy wife – and it is blackly humorous, e.g. a shaggy dog secondary narrative featuring Scatman Crothers that raises a snigger – the sucker punch to the gut, despite the thematic depth and nuance that Kubrick layers, is that the abiding memory is emotive not intellectual, of the fantastic sound design of the child’s tricycle rumbling on hard floor then weirdly going to semi-silent pedals being pumped as he hits carpet, as the camera pursues him and the music drones to create a sense of impending dread.

BLACK NARCISSUS

Black Narcissus (1947) is a tale of sexual repression in a remote convent in an exotic location, which is the risqué hook, a salacious surface (as far as the times would allow) to pull in the punters; however, despite the vague whiff of an exploitation film in its premise, it is nothing of the kind, but rather deep-thinking and cinematically beautiful (with a 1940s sexy twist) – underpinning Black Narcissus are two major themes: a questioning of religion, and attitudes towards foreign cultures – Sister Clodagh (the luminous Deborah Kerr, who was anything but a nun in real life) leads a mission to open up an Anglican convent in the Himalayas when the local ruler allows the religious Order to use an empty building on a windswept mountainside (literal and symbolic) along with opening a school and hospital for the locals; but no one has mentioned that the building used to be a seraglio (a harem) – the local Englishman / colonialist / representative (David Farrar) greets the nuns, exposing his thighs in shorts and acting with little regard for religion, there is a holy man on the hillside who just sits there and posits another religious take on life, the locals are puzzled by the nuns strange vocation that is so different from their reality, and the ‘young general’ (Sabu) becomes infatuated with a local girl who is deposited in their midst to look after (Jean Simmons) and who is unruly and sexual, earthy as opposed to spiritual – the nuns slowly break down in the face of these challenges to their way of thinking: Sister Clodagh starts to reminisce about a failed romance in her past, Sister Philippa (Flora Robson) stops gardening and stares wistfully at the view remarking on how the air is different where they are, and Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron) goes off the deep end into bad girl territory – the bad girl gets her comeuppance, but the magnificent Powell and Pressburger who directed, produced and wrote the screenplay (based on a novel) are clearly using this as a smokescreen to mask their sympathies pulling in the opposite direction, tearing at the righteous self-validity of the Western and Christian values of the nuns – it won Oscars in a time when non-American films didn’t win; but it also suffered cuts in the US, which indicates how it trod the line of decency and played with the attitudes of its day – most impressively, it was entirely shot on a stage in England and the backdrops are all exquisitely painted (long before CGI) to create a heightened imaginary Himalayan country to match the febrile themes, for which Alfred Junge (the art director) deserves the highest praise – and it was shot by Jack Cardiff, a fine cameraman who went on to direct himself – gorgeous to look at and profound in its themes, Black Narcissus is at the peak (pun intended) of the many wonderful Powell and Pressburger films: simply extraordinary and magical.

YOJIMBO

Yojimbo (1961) is a seminal film of mercurial pleasure: one of many samurai pictures by the great Japanese director, Akira Kurasowa, it can be argued that it marks the birth of modern action films in general (remade several times in different settings) and is the inspiration for gritty westerns (unofficially remade as A Fistful Of Dollars, the first spaghetti western) although it is swords rather than guns – a ronin (a samurai without master) walks, by chance, just wandering as a ronin does, into a town with two competing gangs, and starts a bidding war for his martial services: much violence and nefarious plots ensue – why is it so revolutionary in terms of the history of cinema? because it introduces us to various ideas and gimmicks as a unified plot, a template that has since become common in action films – the ronin (Toshiro Mifune) sits in the middle of town while the gangs inhabit either end, and he plays them against each other (e.g. Miller’s Crossing) – the town is run-down and muddy (e.g. Unforgiven) – the blood count is high, introduced at the start by a dog running past the ronin with a severed hand in its mouth, escalating to sword fights and so on (every action film now has a bloody and high body count) – the central character is an anti-hero, doing right by doing wrong, violent but on the side of the small man, full of twitches and anti-social behaviour (e.g. John McClane in Die Hard) – the ronin is also the original ‘man with no name’ as he looks out of the window and says what he sees when asked his name; and when the ronin is called to act, his killing is swift and smooth, just like Clint Eastwood except with a sword – it is not that these ideas did not have predecessors nor came out of nowhere, there are earlier examples and progenitors, but Kurasowa gives them a modern twist and meshes disparate strands of idea together into a format that has been copied ever since – it is interesting that Kurasowa said his key influence was film noir, and Yojimbo shares that seedy vision of low-life and places it in an action setting, borrowing blood from the relaxation of censorship in the era – it could be said that the subtext is about local corruption, but it is really just an action adventure with a brilliantly envisaged scenario: at the end, the town is peaceful because everyone is dead not because political issues are resolved – it is shot beautifully in a wide-screen by Kazuo Miyagawa; with a score by Masaru Sato that anticipates (in a Japanese way) the use of music as a commentary on the action that Morricone would make his own – Yojimbo is masterful and influential.

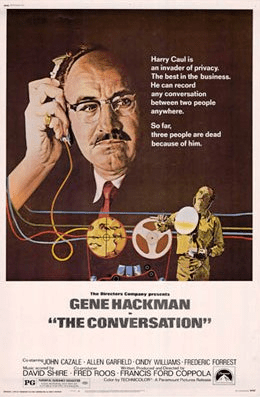

THE CONVERSATION

The Conversation (1974) was directed by Francis Ford Coppola at the peak of his critical and popular acclaim, winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes (in the same year, The Godfather Part II, also directed by Coppola, won Best Picture at the Oscars) – The Conversation is a lesson to all modern film-makers as it focuses on gradual revelations, inwardly on small details, not on expansive action or explosions, while retaining a broad cinematic ambience: it is mesmeric as a result – a surveillance expert (Gene Hackman) has been hired to watch a man and woman, possibly cheating lovers, with the woman the wife of a rich man who leads a big business: Hackman bugs the lover-conspirators as they have a conversation in a noisy public place; and then he struggles to put the conversation together afterwards, as snatches of conversation wander into electronic burble as the targets go out of range of one microphone and into another or their voices are drowned-out by other noises – the scene he has surveilled is repeated throughout the film, from different viewpoints and ear-wigging posts, or with alternate visuals of the ‘lovers’ meeting, as their conversation becomes clearer in snatches as the expert works on it with his technologically advanced recording devices; but each bit of clarity changes the import of the conversation – the scene of the conversation is repeatedly intercut with a linear narrative of the expert interacting with his employer and the ‘lovers’ at their business offices, and his private life (e.g. of Hackman listening to the tapes of the conversation in his deserted workspace, a space which reflects his deserted inner life), a narrative which also becomes more relevant as the conversation is unpicked and things are revealed – it thus becomes a study of perspective and knowledge as disjointed fragments inform and slowly build up, creating a subtle mystery and crypto-detective story that reaches a despairing resolution – but it digs deeper philosophically, into the solipsistic nature of being, with the communications ‘expert’ hearing but not listening or understanding, he sees but does not perceive, unable to grasp the bigger picture as he is locked inside his own personal hang-ups and concerns: he has a withdrawn insular nature, refusing to talk about himself and wary of interaction with others, which means he has no understanding of others (and life in general) and is taken advantage of as a result, despite his paranoid caution (surveillance paranoia is very 1970s, taken to its nth degree here) – Hackman’s understanding of communication is thus mechanical, repetitive not receptive or interpretive; and the film is full of thematic commentary on the limitations of the fixed individual vs an unfathomable broader context, on mis/interpretation, perspective, mis/communication, misunderstood motive (etc) that goes beyond the narrative to being a general thematic meditation on the separated nature of each human being – further, it is one of a very small group of films where the sound design is something to enthuse about, with much credit going to Walter Murch (who also did a chunk of the edit), as the sound of the conversation is brought into focus and pieced together via the best and subtlest sound effects of the time – a fantastic cast and crew is the cherry on top of a profound and very clever film about perception versus reality.

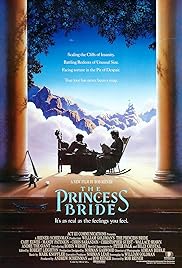

THE PRINCESS BRIDE

The Princess Bride (1987) was directed by Rob Reiner in the middle of his hot streak of fine comedic and/or feel-good films, during the 1980s and early 1990s, between Stand By Me and When Harry Met Sally – if you are looking for depth of meaning then look elsewhere, for the aim here is just mischievous silly fun, delivered in joyous spades; a parody of swashbuckling fantasy adventure films, with any subtext the standard underpinning of every romantic-nobody-vs-evil-ruler fairy tale (parodied) – however, there is more to it: the genius of the film lies in its self-reflexive mirroring of itself and the genre it inhabits, i.e. the genre it parodies is close to self-parody itself (e.g. several Errol Flynn films) and The Princess Bride simply over-eggs what is already the tongue-in-cheek of the genre – thus we get something taking the piss out of something that is already taking the piss out of itself, and the film nearly ends up being a straight take on the genre (but not quite), flipping right round to where it starts from (with more gags and an extra touch of absurdity) – to add to this post-modern take on genre, the whole story is filtered through a framing device, an unreliable narrator, with grandad telling his grandson the story, complete with interruptions of the narrative by the grandson, removing the viewer from the mythical world of the story with inserts of ironic ‘real-world’ questions about the probability of the tale – there are also a large number of jokes and catchphrases to get into, something no cult comedy can do without, which fans of the film are fond of shouting at the actors (ask Wallace Shawn about being told everything is ‘inconceivable’) – the screenplay is by the celebrated writer William Goldman, based on his own novel; and the soundtrack is by Mark Knopfler, restraining his more rocky inclinations and making the electric guitar sound almost medieval; and the cast includes numerous famous faces popping up in cameos to enjoy, such as Billy Crystal or Peter Cook – critically well-received, it had a ho-hum box office; but it became a cult film with video and DVD releases, and has become a favourite film of many people, never topping but regularly on best-of lists – self-satirical comedy and jaunty adventure, the film is enjoyable on different levels, so that both adults and children will be engrossed – worthy of the adoration it inspires in some.

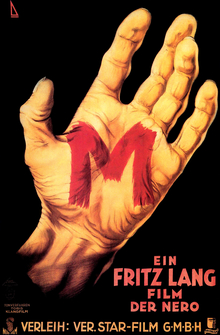

M

M (1937) was cited as the favourite of his own films by the great director, Fritz Lang; and it is considered one of the best films in the history of cinema by critics and fans alike – it is remarkable on two fronts: its technical and narrative innovation, and its thematic social commentary – a German expressionist film made during Nazi rule, it had a tricky way to screen: some of the real-life criminals used in minor roles were arrested during the shoot; and then the censor delayed its release, which Lang feared was the censor thinking that the film was a criticism of the Nazis (which it kind-of is) until Lang showed those barring the way the script and found that their objection was limited and on the surface, a reaction to the original title (Murderer Among Us) – however, if his thoughts were close to the script for M, which he co-wrote with his wife (Thea von Harbou), it is no surprise that Lang fled pre-war Germany to Hollywood; and his subsequent, and final, German film’s subtextual critique in The Testament Of Dr Mabuse (also recommended) would be an even more open-veiled attack on the Nazis – M is daring thematically: ostensibly about a ‘child murderer’, obviously a person we would call a paedophile nowadays although Lang avoids any sexual content, the focus is really on how others respond to the murders: the police investigation into the killings, which has been imitated to convention in numerous other serial killer movies and provides the narrative thrust, political pressure on the investigation which both helps and hinders, and vigilante action and mob fear as people are whipped-up into a frenzy of finger-pointing – but what makes it thematically astounding is its balanced judgement of the murderer’s actions: he pleads his case of uncontrollable urges (Lang met actual killers for research) before a kangaroo court of criminals, who have captured him not out of social conscience but because he is bad for business, some of them being murderers themselves (though not of children) without the excuse of being mentally unbalanced – thus, the film argues that the offender should be locked-up and treated not summarily executed, and we should not be led by mob fear and brutal self-interest (the Nazi references) – it ends with ambiguous dialogue from one of the bereaved mothers, accepting the fate of a confused situation yet advocating vigilance of children: the fatalism of this ending is something that permeates much of Lang’s work, the inevitable and chaotic forces of existence crushing individuals – but it is so much more than themes, it is also a technical marvel – his first film in sound, there is a merging of sequences that could be silent with (predominantly) sequences that could be from much much later films, with natural-ish acting, nicely framed camerawork with innovative tracking shots and angles, and fantastic set design – in particular, the use of sound was his first film using the new technology and is astoundingly experimental for its day: although the sound technology was primitive and limited (e.g. no soundtrack punctuating the action due to lack of tracks), Lang has background and overlapping noise to create a whole world of real sound, unlike its more stilted contemporary films; and then he has the murderer whistle a tune from Grieg’s Peer Gynt as a leitmotif that announces who he is, a trick that has since become common in films (i.e. a character is identified by the music) – in addition, the murderer is played by the bug-eyed Peter Lorre, announcing his creepy talents to the world – M had a mixed reaction on its first release, although successful (as Lang was a name that sold), and was then cut by twenty minutes for release in the 1960s, a version that became ubiquitous; but it has since been restored to its original form (or as close to it as is possible) and this is the version that should be sought out to fully appreciate this masterwork … but what is the significance of the symbolic ‘M’?

NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD

Night of the Living Dead (1968) is the ground zero of modern horror films, introducing a whole new level of gruesome following the relaxation of censorship during the 1960s – in 1968, when it was released, horror films tended to involve rubber masks in unreal settings, tame fare that was even shown at matinees to teenagers (and younger): imagine the shock caused by this film when it was shown at matinees! there was moral outrage – but time changes perspectives and it is now lauded by the mainstream, in ‘halls of fame’ etc, which has much to do with the financial success it achieved (yep, cynicism): made independently, it grossed 250 times its small budget and set the template for the future methodology and cheap financing of gory horror films, copied to death (yep, pun) – a small group are trapped in a building in the middle of nowhere, thus reducing costs on locations, sets and actors; the small cast of characters are killed in increments, in violent ways (as per many other low-budget horror films since); it was shot quickly on cheap film; lead actors double-up as zombies and other actors were part of the production crew; inexpensive stock music was used and fed through an electronic mangle to make it eerie; and the special effects were cheap and improvised (e.g. chocolate sauce for blood, which looks right in black and white) – and then it is the film that created the modern zombie mythology, although they are referred to as ‘ghouls’ in the film and no one uses the z-word (George A. Romero, creator and director, didn’t even consider them zombies at the time): there were zombies before this, of course, but they were the tame spirits of Caribbean origin, as in I Walked With A Zombie, whereas this film gave us flesh-eating threat and disease – it was the first of many zombie films using the flesh-eating template (and law suits over the rights) – but it is more than seminal and lucrative, it is a highly intelligent film too: the ropiness of the low budget is used to add to the sleazy horror feel, with the photography sometimes overexposed or the soundtrack distorting like a buckled vinyl record, giving it a gritty realism that the narrative belies – there are also subversive themes, much in keeping with the cultural revolutions of the time: the lead role is played by a black man (Duane Jones) who is shot by a red-neck, those in power and the media do not know what is happening as social order disintegrates, the taboos of polite society are broken down in the name of survival, it can be read as an allegory for Vietnam, the zombies can be read as a satirical side-swipe at the ‘silent majority’ of Nixon, etc – however, in the end, it’s about being human and how people respond to crisis (we are all socially conditioned flesh-eaters) – it cannot be described as a b-movie, although it has the tone of one, including schlock riffs on 1950s sci-fi (e.g. it’s all due to radiation from a space probe to Venus), it is far too deep and enjoyable for that, with the action snowballing to a cynical conclusion – “They’re coming to get you, Barbara!”

THERE WILL BE BLOOD

There Will Be Blood (2007) is the finest film directed by Paul Thomas Anderson (to date) who has been described as a modern auteur as he makes unconventional films that have the topics and style that are near-impossible to get made in the mainstream Hollywood studio system, but he manages to get his irregularities made with relatively large budgets, a good critical reception, and commercial success (nb. he should not to be confused with his namesake and contemporary, Paul Anderson, a director of deliberately trashy action movies) – Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) begins the film prospecting for oil and finds the mother-load during a nearly silent opening sequence (no dialogue, bravely, for a substantially long time); then the bulk of the film is spent with Plainview trying to convince the locals to sell their land, with the aim of ripping them off so he can be inordinately rich; with a shocking coda at the end – it is a deceptively simple narrative that hides a depth of meaning, a thematic assault on Individualism and Capitalism – firstly, on the surface, it is a tale of rapacious avarice, greed leading to social isolation, of both Plainview and his local nemesis, the preacher at the local church, who uses the religious sway he has over the local population to become rich himself, i.e. as a consequence of Plainview’s laser-like and bitter focus on wealth, he struggles when he has to rely on interpersonal skills to negotiate with those who will not simply take his money, his adopted son leaves him on bad terms, and he has no friends, ending up alone in his mansion, bought with the wealth he makes, with his servants (and the preacher’s tale is a distorted mirror of this; but it is primarily Plainview’s story, of a greedy and ruthless man who treats others with contempt, whose bottom line is the acquisition of more and more to the cost of his private life) – secondly, it tackles the often selfish nature of social relationships with everyone after their own ends, not just Plainview and the preacher but also the locals who the preacher urges to hold out for their homes, land and more (so he can up the price for himself) in an attempt to advance themselves (being deceived by the more selfish); forcing Plainview into interacting with the small town life he despises in a decidedly two-faced, selfish way – thirdly, it is a devastating critique of the US national psyche: at the heart of the film is a conflict between Capitalism and the Church, which are the twin pillars of the US, with the nasty Capitalist winning a pyrrhic victory in the long-run, but neither side coming out looking good, with the religious lead being intractable at first and finally revealed as a hypocrite; which detail-by-detail builds up as an allegory to address the dark sides of the American dream on which the nation has been built, its values and history: the rich exploiting the poor, violence, evangelical religion, community vs enterprise, power in interpersonal relationships, etc (the critique of the US runs very deep) – further, There Will Be Blood is gently stunning, visually and aurally: the film frequently deals in montages of finely shot imagery (by Robert Elswit) to a subtly melodic soundtrack by Jonny Greenwood (from the band Radiohead) in a classic example of the storytelling dictum of ‘show not tell’ (reminiscent of the way Sergio Leone narrates primarily with image and music in his Spaghetti Westerns, creating visuals to go with Morricone’s striking music) – there is a fine cast, with Daniel Day-Lewis giving a monster performance – and the narrative technique is particularly pleasing as it sprawls with loose ends, the focus on scenes that are not connected fully, giving it a real life / realistic feel – a film, already lauded, that will last and grow as large as Day-Lewis’ performance in reputation.

WEEKEND

Weekend (1967) is a film by Jean-Luc Godard; which is an immediate red flag for anyone who expects a conventional film, but it is an exceptional and brilliant film that is significant in various ways – firstly, it marks a transition in Godard’s own film-making, marking the point when he stopped making ‘stories’ and became fully avant garde: he retains a sort-of narrative via a murderous road movie and his love of noir, but takes it off on surreal vignettes (worthy of the great surrealist film-maker, Bunuel); with the whole being almost incoherent, if it were not for the contemporary social satire of the themes acting as glue – secondly, it is historically fascinating: made in 1967 with the student riots of the 1960s close-approaching, it is a piece of agit-prop that squarely aims its critique at ‘normal’ society, with the bourgeois representatives of Capitalism being so violent and rapacious that a [youthful] revolution is underway (the whole film is against a backdrop of burning cars as a bourgeois couple go on a weekend car ride in order to kill the wife’s mother, in order to get the inheritance) to the point at which, by the end, the revolutionaries are eating the rich, rather than the usual ‘eat the poor’ of anti-Capitalist slogans; meanwhile it goes on numerous other satirical side-swipes at society, like colonialism in a brilliant section where one refuse collector (refuse is symbolic here) speaks about Algeria while another is in visual, staring at camera in a technically daring sequence, or it satirises hippies via an Alice in Wonderland skit, or it subverts French history via a man in Napoleonic uniform expounding-ranting from a book, etc – thirdly, it is at the cutting edge of post-modernism, with a deconstruction of cinematic narrative to come up with something completely alternative, a self-reflexive nature that calls attention to the fact that it is a film, and ending with a closing caption of ‘The End of Cinema’ (as we know it, traditionally) – fourthly, it is technically outrageous, e.g. a traffic jam that goes on forever to a soundtrack of horns as the protagonists work their way past an array of stuck humanity, or an endless 360 degree pan that does 360 more than once as someone plays Mozart and stops occasionally to explain Mozart’s life, or a car crash that is done by simulating the film going wrong in the projector, or random intertitles that are part-absurd and part-disordering, or the soundtrack music suddenly swelling louder so it drowns out what a character is saying then disappearing to let the speech continue, etc – to cap it all, it is shot handsomely by the great cinematographer Raoul Coutard – there is an issue with Godard’s treatment of women, which is very much of its 1960s time and problematic: his films do have strong female leads but he also often treats them as sexual objects, especially a disturbingly casual ‘comedic’ scene about rape here (which can be seen as a shock tactic to reveal the callousness of the rich, but it is very uncomfortable) – overall, however, this is a landmark film that defines a moment in history and explodes conventional art – is it watchable without a coherent conventional narrative and absurdist touches? unbelievably so – cinema would never be the same again.

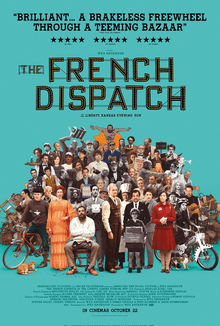

THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) is the high watermark of director Wes Anderson’s career: always worth watching, his idiosyncratic films have a hyper-real feel to them in a style he has made his own – The Grand Budapest Hotel moves at a break-neck pace, merging his work with live action and his work with animation into one product, seamlessly moving from one to the other, creating a cartoon-like ‘real’ world (which recalls the films of Frank Tashlin and the Coen Bros at their most zany) – it is also a comedy that makes you snigger frequently with occasional laugh-out-loud moments – the film is usually talked about in terms of its technical accomplishments: the merging of live action and animation, with the animation sometimes deliberately obvious to obscure the brilliantly imperceptible use of miniatures etc that create the grandeur of the hotel and sweeping landscapes, rushed past by the furious narrative; the width of the screen (beautiful camerawork by Robert Yeoman) altering to reflect the different time periods of the story, as a signifier of the date as the narrative hops back and forth between decades; it has a cleverly subtle gaudy design and colour scheme that heightens emotion; and an entire fictional world of inter-world-war mittel-Europe is created, recognisable as historically accurate while being non-historical – and then there is the sheer fun of watching a stellar cast, the best of contemporary acting talent (showing a high regard for Anderson in the film industry), acting like children in a madcap narrative with numerous twists and turns that never lose you – yet underneath the humour is a darkness that will pass most by, and it is like a comedic version of The Shining in some aspects: both films have a hotel in the mountains symbolically representing the history of mankind and atrocities perpetrated, and there are numerous shots of hotel corridors and symmetry of visuals that the two films have in common (the past leading to and recurring in the present) – as such, hidden behind the fun surface is a poignant thematic core of depth, a tale of ongoing persecution, of an effeminate man and his immigrant sidekick pursued by Nazis and, one of them, eventually executed by the Soviets: in fact, everyone ends up dead, except one character who manages to hold onto the eponymous hotel from his wealth once the autocratic States have taken their bite, and continues to sleep in his monastic cell-like room despite being the owner, a melancholic person detached from all else, a shadow of a man beaten down by bad actors and the State – but the main theme is about romanticisation of the past, of memory: the tale is narrated through a series of distancing devices, with the story told at third-hand at best, allowing for the amiable distorted comic book style but also enabling a commentary on how we sanitise and change the past to fit our own vision and prejudices (dreams from an impoverished later state), e.g. the bad people of the inter-war period become slapstick fools rather than the sinister people they really are, filtered through nostalgia for a significant time of friendship and romance and selective memory – and the above summary just begins to dig into the technical and thematic complexity of this exceptional film, which deserves to be seen more than once.

PANDORA AND THE FLYING DUTCHMAN

Pandora And The Flying Dutchman (1951) is a cult masterpiece by Albert Lewin – a director, producer and screenwriter that is not well-known, Lewin was a Hollywood auteur when the studio system was stamping out such bright sparks: the reason he was able to follow his star is that he was an industry insider with the ear of those in power, so he was initially given a degree of freedom to experiment as a favoured employee; and then his films made money, so he was given more latitude; and, as such, given the lack of restriction by studio formulae, the small number of films that Lewin made are generally worth seeking out for their unusual nature – Lewin had ‘educated’ pretensions (except his films are not pretentious because they achieve their aims) and Pandora And The Flying Dutchman is the most rich of his films in ‘high art’ allusions, allowing it to be read in the same way as a novel, with a tapestry of themes and subtexts about eternal love, obsession, the supernatural, etc – set in a small and aptly-named Spanish village by the coast, Pandora (Ava Gardner) is a woman that her suitors will do anything to prove their love for, in macho ways (racing cars, bull fighting, suicide): she is kind to her suitors, but distant and uninterested, until a mysterious and enigmatically attractive stranger (James Mason) anchors his boat in the bay – the story is told in flashback by Pandora’s friend and admirer, Geoffrey, who breaks the fourth wall to directly address the audience early on, and then proceeds to narrate things the character could not possibly know of (heavy-handedly overdoing his ‘foreboding’; but the over-emphasis works, in sympathy with the fatalistic hyperbole of the whole film, raising a smile from the viewer) – Geoffrey is engaged in finding ancient artefacts and metonymically represents the whole film: like him, the film is digging up ancient myth, classical and literary allusions crunched into a melange of references from separate sources (e.g. the title: Pandora references the woman who opened a box to release the evils of the world, and the Flying Dutchman references the ghost ship that is doomed to sail the world as a harbinger of disaster) – the thematic allusions are often mismatched and from different cultures, but Lewin is quite deliberate in this and knows what he is doing metaphorically and thematically: with little regard for fidelity to original myth, he plays with the classical imagery in a coherent way to rise above any possible mess of mismatched references, creating something magical with suspension of disbelief at its heart – the glue for all the references and the motor of the film is a Freudian subtext (very 1950s cinema), i.e. Pandora is symbolic of desire, the macho actions of her suitors are what people will do to achieve their desire; but, as Freud will tell you, desire is unattainable, as once you achieve your aim then you are replete and desire is no longer, or you never reach it; so, the desired true and eternal love is a myth (the Flying Dutchman) and his arrival inevitably leads to the death of the object of desire (chew on that!) – romantic ‘eternal love’ is a myth, undercut by Freud (yet the film remains terribly romantic at the same time) – the stately editing and sometimes stilted acting enhance magical themes, as the narrative winds and digresses in a satisfying way, and there is a fine supporting cast – the soundtrack is notable, with Gardner, the woman of every man’s desire, often overdubbed to give her a breathy-unearthly ear-caress voice, even when on a beach – and, most wonderfully, it is all shot at subtle angles and with flowing camera movement in that dayglo colour of the late 1940s / early 1950s by Jack Cardiff, which gives it a vibrant and beautiful look; with sets and back-projections adding to the unworldly visuals – absolutely brilliant.

PAN’S LABYRINTH

Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) was acclaimed by critics and audiences alike, making the director (Guillermo del Toro) a ‘name’ in the way Scorsese or Hitchcock are, sending viewers back to reevaluate his earlier films and eagerly await his next film – del Toro is a playful filmmaker, wandering between more intelligent fare to directly over-the-top entertainment, leaning more heavily one way or the other but never giving way to one inclination alone, always a mix of thought and entertainment: his for-the-money films have hidden depths (even Blade II) and his ‘serious’ work has fantastical elements – Pan’s Labyrinth is a perfect modulated balance of del Toro’s two leanings, harking back to the magical realist themes of his earlier film, The Devil’s Backbone, in that it portrays a nation (Spain under Franco) through realist microcosm and magical fantasy – a Mexico-Spain co-production (del Toro is Mexican), the film is set in 1944 during the early years of Franco’s fascist rule over Spain: a young girl and her pregnant mother arrive in a region where her ‘new’ father is the brutal fascist captain fighting rebels holed-up in the wooded mountains, and the girl meets a faun in a cave-like labyrinth near the fascist compound to discover she is a reborn princess from the Underworld (or does she? it is never clarified whether the fantasy is real or in the escaping mind of a young girl) – so, febrile fantasy mixes with harsh reality as the girl goes on a quest to reclaim her place in the Underworld while civil war continues around her – in national allegory, there is the savage fascist captain (a terrifically sinister performance by Sergi Lopez), the sick mother who submits to fascist rule out of necessity, an escape into fantasy to evade the horror by the young girl (who is eventually crushed), the subterfuge of resistance, and an eventual return to the King of the Underworld: in essence, the history of Francoist Spain via metonymy – and the fantasy elements are wonderful, never seeming out-of-place being dark ideas (e.g. the monster with eyes in his hands) to match the darkness of the torture (sometimes literal) of the real world – the fantasy has deep currents too, on top of the national allegory, with del Toro feeding off the Greek and Roman myths of fauns (not Pan really) who are creatures of countryside and mountain, slightly untrustworthy but generally beneficial, linked to labyrinths and fertility – and then there is the personal, the good and bad of individuals, deeply affecting, raising a tear in the eye at the end – a labyrinth of the mind and interpersonal relations, a labyrinth of national society, a labyrinth of myth and meaning – add to this some masterful technical skill: in particular, the way the beautiful camerawork (nod to Guillermo Navarro) is constantly gliding sideways, never zooming nor too fast: the prowling of shy magical creatures as well as the prowling of the humans at war; with the constant sideways camera movement allowing for well-disguised screen wipes as trees pass cameras with the characters walking in different directions on the other side of the tree, suggesting time passing yet not passing, both magical and real – generally regarded as one of the best, if not the best, film of its year and director.

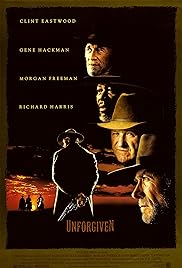

UNFORGIVEN / THE QUICK AND THE DEAD

A modern Western double-bill; with both films playing with the genre, but taking the genre in opposite directions in updating it – Unforgiven (1992) was a huge success and garnered several Oscars for Clint Eastwood, including Best Picture, which is likely due to a sentimental vote for Eastwood’s status as elder of the Western coming back in fine form – it is a ‘revisionist’ Western, ‘gritty’ is the word for it: moral ambiguity permeates everything as the protagonist is as bad as the outlaw turned lawman (Gene Hackman), gunfights are messy and upsetting, the environment is dirty and barely holding back the elements, etc – it is a broader film too: viewer memories likely focus on the splashy showdown finale, but it also contains many passages of travelling or hard living in the harsh but beautiful countryside, and drills down into the theme of companionship – a highly enjoyable film, ignoring a few inconsistencies in the script (if you think about them) and its treatment of women leaving a lot to be desired (the writer, David Webb Peoples, has been over-praised): it is reactionary with a faint nod to a liberal conscience, but don’t let politics get in the way of viewing this entertaining film – but is it ‘revisionist’? with gunfights, revenge, a bad lawman, etc: all the clichés of the genre – what Eastwood does is give the Western a serious surface veneer, dirt and messiness, stately photography and pace: a surface impression of realism while still maintaining tried and tested tropes of the genre – this is clearly revealed viewed back-to-back with The Quick And The Dead (1995), which was a flop at the box office yet is one of director Sam Raimi’s best films – it subversively makes the ‘gritty’ modern Western very comic-strip (cartoon-like action is a Raimi trope); with holes appearing through the bodies of shot people, wacky camera tricks, and parodies of the Spaghetti Western form (incidental characters show their bad teeth, the soundtrack often mimics the great Morricone scores, etc) – credit to the writer, Simon Moore, in that he reduces the Spaghetti Western to the big moments of gunfight, with a series of showdowns taking place as part of a deadly competition – there is a fine cast of gunfighters (Russell Crowe, Leonardo DiCaprio, etc), with the bad Marshall, Gene Hackman (again), dominating proceedings; and, subversively, the main protagonist is female (Sharon Stone, who also produced) – it is huge fun, as though the great cartoon-maker Tex Avery had made a Western – in terms of the genre, it is like a slapstick riposte to Unforgiven, reducing the narrative down to the underpinning Western motifs and perversely making it quick and slick – both films have the same essence, but, in its way, The Quick and the Dead is more honest as it does not hide the truth behind realism – an enlightening comparison in terms of the genre, and both are entertaining viewing.

SOLARIS

Solaris (1972) has the 1960s ‘space race’ between the USA and USSR as its background, with the Soviet authorities wanting a film that showed Soviet superiority in response to 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Solaris is frequently described as the ‘Soviet 2001’ (evidencing the primary influence of Kubrick’s vision, despite Soviet protestations to the contrary) – the director, the great Andrei Tarkovsky, stated his aim was to bring new depth to the science fiction genre, describing 2001 as “a lifeless schema with only pretensions to truth” (ironic, given his own pretensions): his comments deliberately misunderstand 2001, which was an exercise in the physical mechanics of external space, revolutionising SFX in its quest for realism (with a bit of philosophising tacked-on); whereas Solaris is the yin to the 2001-yang, an exploration of inner space, a metaphysical quest into the nature of man and being throughout (with space exploration tacked-on) – films with different focuses, different beasts, much like the east / west binary opposition of the time: the two films changed the face of sci-fi film-making between them, in their own ways – the production of Solaris was fractious, but Tarkovsky was at his best when struggling with collaborators and censors as this remedied his tendency to pretension and over-talkativeness in his films: he disagreed with the celebrated original author (Stanislaw Lem) and his cameraman (the talented Vadim Yusov), the Soviet gateway-keepers for film production forced him to rewrite the script to move more of the film into space (a good move as it is in space that the film really gels), and he needed to make various cuts, particularly to play down the allusions to religion, in the frequently played game of film-makers making fewer changes than requested by the censors to see what they can get away with – still, Tarkovsky needed a success as his previous film had not been released by the Soviet authorities, who had found it untenable politically, so he chose a relatively accessible story and gave way on certain production issues: the result is a film that is both engaging and deeply thoughtful – but he did not compromise fully: ‘meditation’ is the word that most aptly sums up Solaris, which has a zen-like quality to it, with a leisurely pace, reflective (unlike the inferior US remake that turns it into a standard drama in space by quickening the dialogue and edits, naturalising to its detriment) while still being a space epic to satisfy others – a psychologist is sent to the Solaris space station in order to evaluate the reports of a deteriorating situation, only to encounter the same mysterious phenomena as others on the station: the planet that the station orbits is covered by a sea that acts as a giant sentience, sending ‘messengers’ to the station that look like people that have been telepathically grabbed from the humans’ brains, with accompanying memories of the past, wishes and fears; but these messengers are imperfect copies of humans, and do not understand what is happening as much as the humans – it thus becomes a study of the intractable difficulty of understanding the alien, something beyond our frame of reference and comprehension: in fact, the sentient sea is studying and learning about us, not vice versa, with its brain the size of a planet (we are playthings of the universe, not the universe our plaything) – the sea below foams and swirls with bright colours (like something from Barbarella, a comparison that would make Tarkovsky foam) as it ‘thinks’; an occasional glimpse of someone unknown running out of the corner of the eye hints at the horror genre, but it is just unsettling here, suggesting something more beyond our understanding: we meditate on this, as does the film – the external existential collision between aliens, sea-planet and human, is the leaping off point for a meditation on humanity: as one character notes, space travel is not about exploring space but expanding Earth (“We don’t need other worlds, we need mirrors”): humans are navel-gazing and solipsistic, variously each wrapped in their personalised individuality even as part of a common whole, and that common whole of humankind has a group solipsism: the scientists on the space station represent different types of human (and strands of scientific thought) but tell the sentient sea’s embodiment of the psychologist’s dead wife, ‘We are all human’ (reducing complex difference into a simplistic unity) – the film then gives us deeper meditation, the internal existential conflicts inside each man, concentrating on the feelings of the psychologist / lead protagonist: his dead wife who committed suicide, his parents, the place where he grew up, memories, regrets, family, childhood … and love: as described by the film, you are unable to explain but able to experience love (like the sentient sea) – so, perception and (un)reality are filtered by illusion and delusion into non-touchable factual truth and feelings, that may or may not exist; and we are left with the final image of the individual on his island of reality amid the sentient sea of further intelligence swimming around him (a person in society, life for the atomic creature, metaphorically) – to complement the themes visually, the film alters between monochrome and colour, suggesting different states of consciousness or perspective (making a virtue of probable budget restrictions); and the camera is always gently roving with slow zooms, panning and tracking, meditatively, always drifting off the focus of the activity, reflecting the impossibility of keeping your eye holistically on even a small part of life, exemplified when the visuals go into extreme close-up on an ear while the characters talk (this inquisitive camerawork keeps you interested even when the characters waffle) – the design is terrific, giving us a space station that is falling apart with wires hanging out (anticipating the later work of Ridley Scott to add grime to sci-fi) – and the soundtrack is particularly noteworthy: apart from a beautiful use of Bach, most of the soundtrack is electronic (in 1972, no less) and uses ambient bleeps and bloops to create an alien atmosphere (Leonid Roizman take a bow) – a masterpiece that dates yet retains its power, a temporal trick which most artists would give their arms for the secret to achieving.

THE THIRD MAN

The Third Man (1949) was directed by the gifted Carol Reed, with the help of a very able assistant director, Guy Hamilton (who later directed some of the better early Bond films); it was executive produced by two of the biggest hitters in film, David O Selznick (providing American stars) and Alexander Korda, with London Films (the Korda production company) adding their usual skill of delivering interesting films; and, most importantly, it was written by the great Graham Greene, who wrote the story specifically for the screen as he thought Carol Reed had talent as a director (Greene was a newspaper film critic at the time and had seen Reed’s earlier films) – the film sees Holly Martins (Joseph Cotton) arrive in post-WW2 Vienna on the death of his friend, Harry Lime (Orson Welles), to discover that Lime was involved in nefarious dealings on the post-war black market, with Martins’ view of Lime disillusioned and his danger increasing as he probes into the criminal underbelly to find out the truth about Lime’s death; which is played out across a politically divided Vienna, between communist East and democratic West, with wartime allies trying to accommodate each other while still pursuing their own agenda (a comment on Berlin too) – the result is one of the great thrillers, with paranoia and atmosphere created by terrific camerawork, shot beautifully at extremely giddy angles in highly defined black and white by Robert Krasker (take a bow), against a backdrop of a defeated and ruined city (chases take place over bombed-out buildings, the narrative revolves around black market penicillin, etc), alongside a story that moves with pace into the depths of what people will do to survive and the opportunism of criminality, with the narrative moving quickly and lightly, unpredictably complex but never a chore to figure out – what makes the film tick though, the heartbeat of the film, is one of friendship and love wrestling with the awareness of shady dealings in a post-WW2 Vienna that is struggling and cynical (even the ‘good guys’ are not averse to a bit of blackmail to get what they want): a tale of conflicted and murky morality – but what seems to most interest Reed are the paranoias of an alien environment (from the perspective of the visitor, Cotton / Martin): Lime’s sidekicks are wonderfully creepy and ‘foreign’, there is a riff on the Fritz Lang’s M when the faces of a crowd turn ugly as they mistakenly think Cotton responsible for a murder, he is taken on a scary car ride that turns out to be innocent, there are shots of locals watching from windows and street corners (everyone is watching!) etc – however, it is most notable for being considered an Orson Welles film, when he is mainly an absent figure and annoyed everyone during production, as his Harry Lime steals the show: the iconic reveal when he is first seen is a landmark movie moment but brief, and then there is the famous Ferris wheel scene and a finale chase in the sewers: that’s the limited time Welles spends on screen, but he makes an indelible mark (the radio and theatre spin-offs all focused on his character, Harry Lime) – in particular, the only dialogue Welles has is the Ferris wheel scene (who is driving it? the fairground is deserted) when he acts the socks off everyone else in the film, giving Lime a mercurial inner life as he flits easily between sociability and death threats: you are drawn to him, despite his despicable nature – the female lead is definitely drawn to him, being open in the film about sleeping with Lime in a way that would have been censor-baiting, and she ignores and walks past the Joseph Cotton character (technically the lead) in a perfect end, despite Lime being awful and Martins helping with her predicament – and then there is the famous zither music, which is a pleasant ear worm that is unforgettable: no one would know what a zither is if not for this film, and the title music was an international hit – an unusual and exciting film noir in a post-war setting; and a hugely popular success, but not in Austria for some reason.

DUCK SOUP

Duck Soup (1933) is the Marx brothers’ best film and a huge influence on later comedians, particularly its anarchic action, fast pace and slightly surreal aspects – significantly, it was directed by Leo McCarey, who worked with a lot of the early comedy greats and has a wonderful disregard for sense when he wants to make a gag, including sudden edits that would not be included in ‘serious’ films, making him a key reference point on how to approach gag-laden comedies since – combined, the stars, the writers (Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby) and the director, make this film huge fun in a slap-in-the-face way, jolting you to pay attention through sheer energy and idiocy – Rufus T. Firefly (Groucho) is the new leader of the country Freedonia, appointed at the request of the wealthy Gloria Teasdale (Margaret Dumont, the romantic foil and butt of jokes for Groucho in several films) in return for her money to support the poor nation; while Chicolini (Chico) and Pinky (Harpo) arrive as spies for dastardly neighbouring nation Sylvania: of course, chaos ensues and nothing goes to plan, with the three Marx brothers resolutely uncommitted to anything but themselves, leading to war between Freedonia and Sylvania – the result, irrespective of the creators’ intent (they said it was just a simple comedy), is a remarkable satire of politics and war, with recent memories of WW1 and the rise of fascists equally fair game: Mussolini was so offended it was banned in Italy – there are flaws, including a couple of minor racist jokes that would have felt natural in the 1930s, the treatment of women (esp. by Harpo), and no attempt to create a coherent narrative as it speeds from comedy set-piece to set-piece, making the film disjointed; but, outweighing these flaws massively, there are great verbal gags from Groucho, whose speed and delivery is the main joy of any Marx brothers’ film and in overdrive here, there is mercifully brief musical content (hurrah! no Chico and Harpo indulging themselves on their instruments), and there is the famous mirror scene of one character pretending to be the reflection of another (not created by them, but this is the one that is imitated) – of note, it is the last film of Zeppo Marx, who has a side role that does not light up the screen, and the Marx brothers’ last film for Paramount, with whom they were in contract dispute and dissatisfied with – there is a line that can be drawn on Marx brothers’ films: their two most well-known films (ref. Queen album titles) mark the point when they moved from Paramount to Universal and got a bigger budget, which had the impact of watering down the anarchy of their earlier films with higher production values, more musical numbers and plot; and the Hays Code was introduced, which would temper their more risky gags afterwards (Duck Soup includes a pot-shot at the impending Code when Harpo is seen in bed with a horse while a woman sleeps on the next bed): thus their Universal films are more famous but more tame and less satisfying, whereas Duck Soup was their last free madness at the end of a line of constantly improving madcap films for Paramount – it was not as big a financial success as their previous films (perhaps because the studio did not get behind it, with the contractual dispute going on) although far from a failure, it has become revered as their peak and a masterpiece of comedy genius.

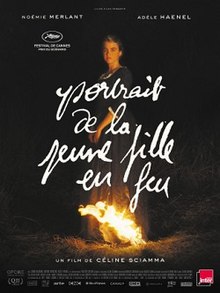

PORTRAIT OF A LADY ON FIRE (Portrait de la Jeune Fille en Feu)

Portrait Of A Lady On Fire (2019) is a masterpiece of feminist art (or should that be mistresspiece?) which has erroneously been viewed as a film about homosexuality as there is a lesbian romance at its heart, whereas the romance is intertwined with brushstrokes that paint a broader picture of the female condition as one of historical social suppression and consequent emotional repression, the main thrust of the film – a female painter goes to an island to paint the portrait of an aristocratic young lady who is to be ‘married off’, and then the film falls into the tradition of artists and models falling for each other under the focused gaze; but here, the talented writer / director, Céline Sciamma, expands the convention to move the ‘gaze’ into a subtext on the female point of view and the inhibiting perspective of her social context, specifically in relation to the 18th century but with themes that can be applied widely to other eras – the only men in the scenario are shadowy figures of report, looming ever-closer to snatch away liberty; and the only physical representation of men is at the start when the painter’s canvasses slip off the row-boat taking her to shore and she has to dive into the sea to collect them herself, after which she is left on a beach to make her way alone, pointed in the right direction: i.e. socially, men see women as inferior and treat them badly, even if their job is to ensure their safe transport, and/or women are quite capable of looking after themselves (or both) – the man of the household being away on ‘business’, the painter’s destination is entirely populated by women: the matriarch who has an air of ‘if it was good enough for me’, the young lady to be painted for her suitor (in secret, as she has proved resistant to being painted for said purposes before), the female artist (masquerading as a companion to veil her secret painting commission), and a female servant – following a failed first attempt to paint the portrait in secret by the artist, the matriarch / mother is called away and the painter comes clean about her commission to the young lady, allowing for a more honest and earnest relationship between the three women who remain (artist, model and servant) – the lady allows herself to be painted to capture her ‘true essence’, which leads to the artist and model having an affair, an affair they know is doomed from the outset: patriarchal society will insist on the lady being married for procreation – the film is also full of swipes at the patriarchy beyond the core narrative: the artist says that she must paint nudes in secret unlike her male counterparts and uses male names to get exhibited, the servant requires an abortion that she seeks with the aid of the other two and abortion-wise local women (not the male who impregnated her), female armpits are less hairy as much as carpeted, etc – essentially jarring, the servant’s abortion subplot is important thematically to give a rounded picture of the suppressed female experience, a male/female rather than a female/female encounter; and the song of the local abortion-women is artificial against the realism that pervades the film otherwise, the only music in the film to provide a heightened atmosphere at a key moment, when the lady literally catches on fire, representing her emotional state (an external symbol of the internal, accentuated by soaring music, beautifully conceptualised) – for a brief period of time, in sorority, while the matriarch is away, the three of them are free of restraint; but only for a brief time, as the suppression of the social order reasserts itself and they separate fatalistically – add to this that the visuals by Claire Mathon are sumptuous and it is deftly edited, and you have a film that is profound and mesmerising despite the slight action: a genuine modern art film classic.

THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD

A landmark of the sci-fi genre and, most importantly, a romp – The Thing From Another World (1951) is an example of the kind of independent production that foreshadowed the breakdown of the Hollywood studio system in the 1960s and 1970s – in an era when the major American film studios had a vice-like control of production and distribution, the great director-producer Howard Hawkes established his own independent production company: he was able to start-up independently because he was exceptional and more-or-less guaranteed profit, his name being a brand mark of quality that was recognised by the public; so the key players in Hollywood gave him latitude, careful not to upset a cash cow (the studio still took a healthy cut of his independent films via distribution, financing and so on) – although Hawkes’ name is not on the credits of The Thing apart from the production company label / his brand, the ‘director’ is a cinematographer and Hawkes directed in all but name, his influence evident throughout with all the tropes of a Hawkes film: e.g. the group dynamics of diverse people thrown together, the action setting where they need to rely on each other despite disagreements, the snappy dialogue, the humour, the rapid pace – so, everything is just right without being precious in any way, as a b-movie is turned into something special and memorable – highlights that are easily overlooked in a tightly-timed film: there is a discussion of the alien’s nature that results in it being described as a carrot from space, which you are led to accept and only appreciate its absurdity on reflection; or there is the brilliant moment of sublime choreography when a door is opened to reveal the alien directly on the other side (reveal, duck, slam! alien hand-trap … all in seconds) – and then there is the unusual (for its day) setting of the arctic location, which creates a creepy atmosphere by enabling perpetual night, cleverly contrasted by the white of snow through the black and white photography – so there is the claustrophobia of shut doors to keep out the cold and long shadows, as they fight the hostile elements as well as the creature (the remote location is also a classic low budget solution to prevent expansion of cast and set) – the remake by John Carpenter is more often seen nowadays (he’s a fan of the film, which appears in Halloween too) but this original is more fun, albeit less visceral – the film closes on one of the great end lines, which can be found on that poster in Mulder’s office in the X Files: “Keep watching the skies!”

THE CABINET OF DR CALIGARI

One for buffs particularly, but interesting to the less film-soaked and occasional viewer who would not usually watch a silent film, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) has been called the first proper horror film, the first cult film, and the first expressionist film – it kicked off the renowned German studio system and ‘German expressionism’ in film, which began to challenge Hollywood until the major talent fled the Nazis and the coming of sound led to English language dominance – there has been much read into it, a lot of it nonsense, so let us unpick it – it has been said that it anticipates the Nazis in its criticisms of authority (Caligari is the head of an institute and uses his position as a defence against charges of murder and manipulating people, a local government official sits on a high chair but doesn’t deign to look down on people and just tells them to wait, etc) but these are simply the small man being at the whim of those with power which is a theme that resonates even nowadays, and the link to Nazism is more hindsight than insight – it is a seminal film in the horror genre, e.g. there is knife murder with a blade similar to the ones used in Psycho and Halloween, Caligari has the power of hypnotism that repeats in films like Dracula, the ‘somnambulist’ (Conrad Veidt) that Caligari influences to commit murder is repeated by Karloff in his portrayal of Frankenstein and the Mummy, etc – but these are things that were popular at the time or well-known in literature, not new: ‘mesmerism’ was a cause celebre of contemporary culture, the penny dreadful literature of the late 19th century was full of horrific conceits and monsters, etc – duality has also been cited as innovative, but this, again, is a staple of horror (Jekyll and Hyde through to The Shining) and the essay by Freud on The Uncanny is essential reading if anyone is interested in the long history and psychological effect of twins, doppelgangers, double lives, etc – and it is a cult film because they struggled to get positive reactions being a German film made so close after WW1, so it took time to take hold – so much for the over-claims that follow the film, not that these do not hold truth in them (just overdone and exaggerated) – what makes the film special is the way it was made and designed (all the creators taking credit for it, so it is hard to specify who actually did it: a team effort) – firstly, it is all done in the studio, unlike other films of the period, and the town where it is set becomes a constantly expanding theatre stage with stage decoration symbolising reality rather than being it – secondly, the town is designed in an expressionistic style, with paintings instead of real walls and streets: there is not a straight line to be seen as the characters enter triangular doors at angles (like the murderer’s knife) or windows have staves that run in different directions, everything distorted and angular, the whole expressionistically representing the deranged minds (a lunatic asylum is part of it) of the protagonists – and the two characters responsible for the evil, Caligari and his hypnotised assassin, are dressed and made-up in extreme ways – so, this is a seminal and influential film in the history of cinema, influencing film noir, horror, the Hollywood studio system, Tim Burton, etc … but, ignore the over-the-top acting style that is common to all silent films and the influence, this is mainly memorable because it is a superbly visual treat.

BADLANDS

Badlands (1973) is a film that is easy to misread as a straightforward on-the-run road movie, merging into the many on-the-run movies that peppered the 1970s; and it has been described as a modern Bonnie and Clyde tale, which conveniently overlooks the fact that no one is robbed (it’s a killing spree) or that the Bonnie of this pair is a passenger not an active participant – the director, Terrence Malick, with his first film, created more than such simplistic readings allow: his subsequent films have revealed his artistic, some would say pretentious, leanings and the thought that goes into his films (e.g. he disappeared from film-making for a decade or two following the flop of his second film, which is less adventure more meditation and therefore not what the public or the money-men were after) – it was only with time and repeats on television that the true class of Badlands became evident, standing apart from its contemporaries, which led to Malick making a comeback as a lauded auteur; but he has never matched this initial effort – Badlands has a flowing narrative, shot beautifully in that trademark natural visual style of the 1970s (with the great Tak Fujimoto as lead cameraman) and we have two fabulous actors in the leads (Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek) at the start of their illustrious careers – but the genius lies in its indirectness – it is never mentioned in the film, but it is about Vietnam: Sheen is 25, good with a gun, finds it hard to hold down a job, the first hideout they make is built with classic Vietnam traps (from which pursuers are shot), i.e. it is a commentary on the soaring violent crime rate caused by veterans returning from the war, who have been trained to kill at a young age but find returning to ‘normality’ difficult – and then there is the indirectness of perspective, with everyone coming from their own angle and not really understanding the other, with the whole narrated from the naïve 15 year old view of Spacek in a blinkered, child-like way – there is also a self-reflexive commentary on film and fame, as Sheen is compared to James Dean and is treated as a celebrity by his eventual captors, even checking his hair in the car mirror during the final pursuit to make sure he looks good for capture – and the action is handled raggedly and realistically, with shootings and car chases that could actually happen, rather than the over-the-top nonsense of modern action films – subtle, even if it can sometimes appear otherwise during the more violent moments, Badlands is a masterclass in non-explicit subtext and oblique understatement.

THE LOVE WITCH

A cult film, The Love Witch (2016) is marmite – some will adore it, some will be less than impressed – it has the potential for someone to think it an inferior film; but, in fact, the film facilitates its own derision and its naff surface is actually superbly crafted skill, i.e. the film’s genius lies in appearing ropey when it is slickly put together in reality, being naff deliberately – it was made in 2016, but it has all the hallmarks of a movie made for the drive-ins of the late 1950s / early 1960s (except the fantastic camerawork) when trash was the order of the day: there is a burlesque bar, dodgy back projection, witchcraft as an unsubtly represented theme (covens were big from the mid-50s to the mid-70s), etc – The Love Witch is a pastiche of this era of trashy movies (rather than a parody, despite making you laugh at times) and ironically plays with the old tropes without being heavy-handed or obvious – the tightrope between awful and fabulous is walked, and the film manages this balancing act beautifully – the acting is stilted but not bad, the narrative is trashy yet intriguing, and the visuals are gaudy and sumptuously gorgeous at the same time – it is also thematically rich, with a commentary on romantic love ideals and images running throughout – overly coiffured and made-up, the lead seeks love through potions and magic, in a metaphorically direct critique of the artifice employed in ‘catching’ someone with feminine wiles: she presents an unreal image of the person underneath and thus fails to find her soulmate – she is desperate for love, lost in the fictions of romantic love found in novels / spell books and social expectations that do not translate to the real world, and she creates problems by following her self-deception: those she bewitches turn into slavering fools, lusting after her in a way she doesn’t want and rejects, killing any suggestion of love as desire impulsively strips them of any agency or sensitivity – and then there are the memories and people from her past that indicate that she has been a sexually used and abused person, yet complicit in creating her own situation, a metaphor for the female in history – and so on … the commentary on romance does not aim for unity of point, but takes it as a theme with numerous digressions on the subject – the film was written, produced and directed by Anna Biller, and she also did the marvellously garish costumes and sets that enhance her peculiar vision, marking her as a talent to watch out for.

THE DISCREET CHARM OF THE BOURGEOISIE

A founding father of surrealism, Luis Bunuel was committed to political and social provocation through the absurd and never made a ‘straight’ film; however, his films can be divided into ones that have a sort-of narrative structure and weird non-narrative ones – The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie (1972) is the most lauded of his ‘weird’ films, e.g. winning the Oscar for best foreign language film, but that is likely because he said he was not going to make more films after finishing his previous one and people did not want to see such a unique vision leave cinema so were encouraging him to continue into his later career – caveat: describing Bunuel as ‘non-narrative’ and ‘weird’ is slightly misleading as there is always a thread of cause and effect, and he keeps you engrossed in the ‘story’ despite the total disregard for conventional cinema – the main thing that keeps the viewer engaged is the black humour, common to all Bunuel; and some have described Discreet Charm as a black comedy, but that is a tautology and a bit like saying birds have wings – the film is constructed around a series of vignettes and digressions, each strand becoming more outrageous until Bunuel has dug himself into a hole, and then one of the characters wakes up from a dream (at one point, a dream within a dream) and everything re-starts – at the centre is a lynchpin that we come back to, as a group of well-to-do friends constantly try to have a dinner party and are interrupted by escalating ‘unreal’ events – Bunuel was interested in the subconscious effect of repetition here: the dinner party, the dreams, an actor who appears in several different minor roles, etc – underpinning the freewheeling nature of the narrative is a thematic satire of the bourgeoisie, which holds the film together: the dinner party of guests maintain a ‘respectable’ demeanour while being promiscuous, murderous and drug smugglers underneath, and running through each vignette is the fear of each individual being ‘found out’ – there is the swipe at the church (a favourite target of Bunuel) which forgives with one hand and holds a gun in the other, the army has its ‘games’ satirised, there is the neo-colonial politics of being nice to the Ambassador of a South American country of dubious repute, etc – a scathing criticism of the veneer of polite society hiding the atrocities that enable a decently wealthy standard of living, done with a cheeky smile and indirectness to make it palatable – and so the dinner party guests are recurrently shown walking along a road, unrelated to the rest of the film: a road to nowhere – the quality is surprisingly high given Bunuel’s unusual working techniques, including very limited direction to actors (who were cyphers to him) and his habit of editing footage while in-camera, but do not expect a highly polished end-product: messiness is part of the point – anecdote: to give you a flavour of the man, Bunuel did not like awards and refused to attend, but he did have a photograph taken of him receiving his Oscar … wearing a wig and oversized sunglasses.

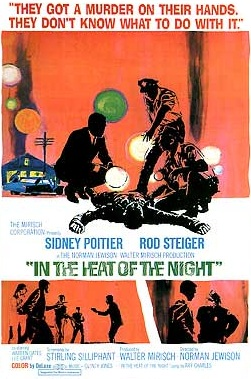

THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR

The Thomas Crown Affair (1968, not the remake) has frequently been called picturesque yet shallow; but this is inaccurate, as it has subtle and profound depths – the surface is glossily shimmering, beautifully shot by Haskell Wexler, with swirling cameras that blur into psychedelic colours at times, idiosyncratic visual coups like the beach house that consists of just a floor and chimney, and the seminal use of multi-dynamic image technique (nod to the inventor, Christopher Chapman) where the screen splits into multiple images in which different strands of action take place at the same time – the leads (Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway) are impossibly glamorous, dressed to the nines and attractive, playing against a backdrop of supposed-to-be-aspired-to wealth – and there is the metatextual glamour of a Hollywood star performing his own stunts and portraying his image on screen, with McQueen driving a dune buggy or flying a glider or, filthy rich, playing polo – however, this surface distracts from the undercurrent – a millionaire masterminds a bank robbery for the thrill, following which a sexy insurance investigator tracks him down and they start an affair: is it a heist movie or a romance? the word ‘affair’ in the title having double meaning, as does the narrative and symbols – e.g. the famous chess game at the centre of the film is really about sex (compare the working class Tom Jones use of eating as a metaphor, from the same period of necessarily using metaphor rather than the sexual act itself) – but the chess game also represents the chase, tracking and catching a criminal, cat and mouse – thus we arrive at the double meaning of the thrill of the heist and the thrill of sexual conquest, the puzzle, being comparatively the same in terms of the emotional heft they bring – and then it goes further, with the couple aware of the others’ intentions regarding the heist but getting romantically involved anyway, leading to an emotionally messy situation, a commentary on the compromises and imperfection of loving and living more generally, eventually leading to the stark choice of professionalism versus personal fulfilment, with an emotionally frustrated inconclusion – that is, the film digs into the ambiguity and non-definite nature of being, self-gratification versus social expectation, and is thus quite meaty in its subtext – it was the second success for director Norman Jewison in two years (the other being In The Heat Of The Night) and both successes had the hidden hand of master-filmmaker Hal Ashby as editor and associate producer – Jewison has a big reputation, but he was only half the artist once Ashby left to direct his own films and his reputation is based on the impetus he got from Ashby, not that you would have been able to tell at the time (hindsight is a wonderful thing) – it also has a wonderful soundtrack by Michel Legrand, his first US film, including that song, Windmills Of Your Mind (best version by Dusty Springfield, by the way).

Á BOUT DE SOUFFLE